Written by Padra Chang ‘20

Maintaining One’s Hmong Culture in the United States

Cultural Practices & Customs at Home:

Growing up in the United States, I was exposed to an environment that my siblings and my parents are not familiar with. It may seem natural to me but to them, it was something new. Growing up in a Hmong household, my siblings and I slowly started to adjust to the American mainstream culture and traditions. We then unconsciously started to celebrate American holidays such as New Year’s Eve, Christmas, Thanksgiving, and many other celebrations. However, my parents disliked these holidays because they are not part of our cultural customs or practices. My father initially criticized our stupidity of following the American holidays but now my father has become more open to these celebrations. Furthermore, my parents were very strict and often reinforced our Hmong culture and customs towards my siblings and me. My parents still believe in the patriarchy system and the notion of respecting the elders. Especially my father, he strongly believes in the patriarchy system and hierarchy of age. He reinforces these concepts every time he sees my siblings and me make a mistake.

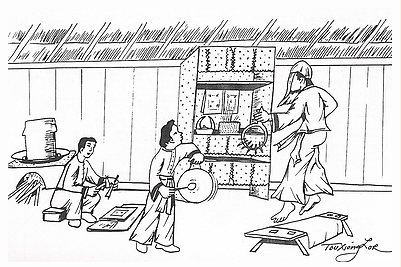

My mother has the role of making sure my sister and I are well-trained to become future housewives. My father will often say that my sister and I are ladies and we should act properly whenever there are guests. We should cook, clean, and help my mother because we are ladies. My sister and I should wear long-sleeves, long-pants, anything that will cover our bodies since it is not proper to have skin showing. We could not hang out with friends or go to their houses because it was considered an American thing; we could not travel without having one of our brothers with us: we have to act proper. These are the roles of a Hmong daughter. On the other hand, my father teaches my brothers to be ready for rituals, Hmong politics, and handiwork. My brothers often have more freedom than my sister and I. They are boys, therefore they should not do any female work as my father always says. However, they are trained to be ready whenever there are events happening in the Hmong community or clan meetings. For example, hu plig is also known as spirit calling. It is a ritual where shamans will call the family or an individual’s spirit back to their body or household. When the spirit is back then we can celebrate and enjoy a feast. It is to help us on a spiritual level to be healthy. I can only speak about certain parts that I know from observing. Therefore, I can only provide small details about the role of Hmong men.

Custom & Cultural Changes:

Growing up in a strict Hmong family, there are customs and cultural practices that certain individuals want to keep and certain parts that other individuals do not want to keep. For example, the patriarchy system. The gender roles in Hmong families can be overwhelming, especially to Hmong ladies. It is hard to follow certain protocols, such as being polite, patient, and submissive. Hmong women went through those steps and it was stressful and difficult. It sometimes impacts women on a mental level because of the overwhelming stress. Moreover, women are not allowed to question their own cultural practices and customs because that is the way it was supposed to be. Some certain individuals would prefer not to practice or keep the notion of gender roles. They want Hmong people to understand that gender equality is not an American notion but a universal concept. They feel men and women are both capable of doing one another’s work.

The mannerism of always respecting the elders is one of the factors that many individuals want to change as well. They think that regardless of age, everyone is still currently learning from one another. Furthermore, they feel elders should respect young people and vice versa. In the Hmong culture, individuals know that respecting elders is a notion and it is a cultural practice, but the concept of elders saying they are always right and the young ones are always wrong, is not always correct. The elders always position themselves to be the authority, which many individuals totally understand and agree, but they believe that both generations are capable of learning from one another. It is about learning and understanding each other as a collective group. In general, situations can differ based on external and internal factors. However, people are constantly learning as they become older.

Customs & Cultural Maintenance:

There are certain customs that some individuals wish not to continue but there are other practices that people wish to continue. There are individuals who strongly want to keep their religious practices, cultural practices, and especially the Hmong language. Individuals may want to keep their religious practices because it is something that resonates with them and defines their identity within America. In America, not many young Hmong people understand or are able to process rituals hosted by shamans, and know how to decipher their symbols or meanings. That is something many in the younger generation are struggling to maintain and others want to keep. In order for Hmong individuals to keep this religious practice, they will try to devote themselves to learning the rituals and practices. They will also need to ask elders questions and be respectful that there are certain things that they cannot interpret for them.

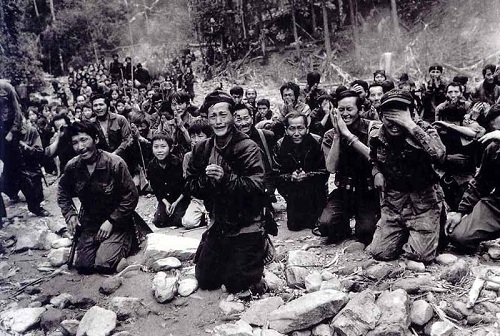

Hmong individuals want to keep their cultural practices as well, but with strong influences from American society, it can be difficult. But many Hmong individuals still have hope. The cultural practice that individuals most wish to keep is the Hmong New Year. First of all, Hmong New Year has already lost its original meaning and purpose. Living in America, Hmong people are often not taught the purpose of it and treat it as an event that people can enjoy, such as hanging out with friends and family, eating Hmong food, watching performances, and many more things. When one is able to understand the purpose of the Hmong New Year, which is to honor our ancestors for the completion of harvest, they might view the celebration differently. This celebration has been going on for years now in Minnesota, but it is important to teach the purpose of the Hmong New Year and its original meaning to the local Hmong population. Then the Hmong people would view it differently than just an entertainment.

Lastly, many individuals, especially those who struggle with the Hmong language, personally wants to maintain the Hmong language. They want it to still be relevant to future generations because it is only taught orally. There are two dialects in Hmong, Hmong White (hmoob dawb) and Hmong Green (hmoob ntsuab). The Green dialect is not commonly spoken anymore so it is especially important that young people learn Hmong Green before the dialect is lost. Historically, the Hmong language is taught orally but now people can learn the Hmong language through certain schools and materials. However, having a conversation can be difficult, especially having a conversation with an elder. There are levels of proficiency in the Hmong language; those that are able to converse with elders and understand their metaphors are considered very proficient. For many young Hmong people it may be difficult to have a conversation with older Hmong adults since they aren’t completely fluent in the Hmong language. However, it is easier for them to converse with other young Hmong people since the conversations are in simpler Hmong. If young Hmong people wish to understand elders and be able to have a conversation with them they will need to speak with elders more and ask them to interpret certain phrases. For future language maintenance, it would be advantageous if Hmong families would try to speak to their children in Hmong and in English. Perhaps one parent speaks Hmong and the other speaks English, in order to not lose the language. To lose the Hmong language is similar to losing one’s own identity, especially in the Hmong culture.